This is a reposted article from my diet coach and bro at Renaissance Periodization, Michael Isreatel.

Mike liked my first entry so much that he shot me this over, and I wanted to use it. So without further ado....

What do the Best Know?

In the strength and physique world, especially in the sports of Powerlifting and Bodybuilding, everyone looks up to the best. Those with the biggest lifts or the biggest muscles are sought after as sources of inspiration and motivation. In addition, the top performers are also looked to for ideas on performance improvement. Lifters, especially young and impressionable ones, look to those who have reached the top for training, dieting, and supplementation strategies, tips, and tricks. While it is rather straightforward to look up to these athletes for motivational purposes, looking to them for training/preparation knowledge is a little more complicated an endeavor. And it’s not the act of seeking out this knowledge that’s complicated. What’s difficult is the interpretation of the advice received.

With muscle magazines aplenty and especially with the advent of the internet (personal websites, YouTube, Facebook, etc…), training advice from the pros is easier than ever to find. However, the value of this advice is questionable. Why, you ask? Don’t those who are at the top necessarily know how they got there? Doesn’t having climbed to the top mean being able to tell others how to do the same? The answer is… maybe.

The truth is a little murkier than would be ideal, but that does not mean it’s nonsensical. Essentially, maximal achievement in any sport, particularly in ours, is a multifactorial outcome. In order to get to the top of the strength or physique world, a number of things need to be in place. When we look to athletes for advice on training, we sometimes make the assumption that their preparation (their program, their diet, their supplements) was the biggest factor in making them a champion. However, there are in fact three determinative factors in performance (especially in sports that require such a long preparatory phase as the strength/physique sports). They are genetics, preparation, and chance, probably in that order of importance. When taking a critical look at the advice of an accomplished athlete, the intelligent consumer of information must consider all three factors before making any conclusions. Let’s take a look at the three factors, in reverse order.

The element of chance is not often discussed in Bodybuilding and Powerlifting success, but it is nonetheless critical. It takes some luck to avoid the kind of career-ending injuries that are always around the corner with the kind of training it is necessary to engage in to become the best. Many a promising lifter has been derailed by injury, accidents, and other life circumstances beyond their probable control. Just think Paul DeMayo and Vlad Alhazov. It takes some luck to rise to the top of any endeavor which requires the preservation and continual improvement of such a fragile thing as the human body.

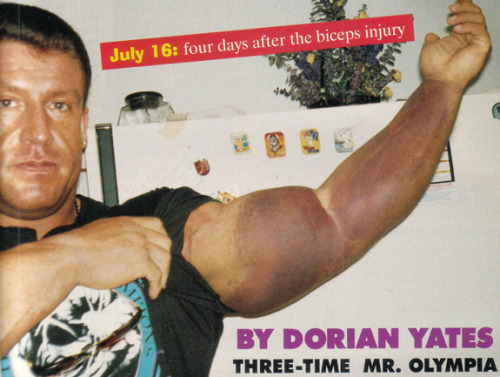

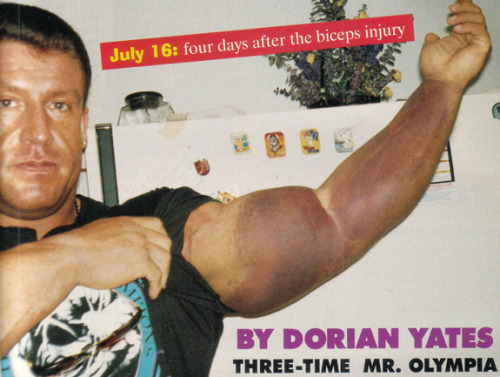

Perhaps all of the best in our sports are not those with the best genetics for strength and growth, but are those that are the most injury-resistant, or just plain lucky? While I consider this possibility unlikely as a major explanatory factor (think the multiple muscle tears and comebacks of Dorian Yates, Branch Warren, and Matt Kroczaleski), it does play a role. Outside of resistance to injury and the proneness to living dangerous lifestyles, chance has a very small role to play in the examination of advice from accomplished athletes.

Notice the plural on athletes.

When taking in information from many athletes, chance events in their rise to accomplishment by definition cancel each other out, and what you get is a non-chance remainder of similarity between the athletes being examined. Of course the contribution of genetics has yet to be teased out, but at least the chance component is mitigated with sufficiently large numbers of athletes being listened to.

There is, however, a caveat to be made here. The plurality of information is very important. If you take the advice of one or just a few champions, attributing their success to their tips or tricks, you may be committing the error of misattribution. With one or just a few sources of information, chance may very well play a large role in the outcome, and you don’t need someone else telling you to do something by chance… you can do that on your own! To sum up, chance does play a factor in strength/physique sport success, so be careful when you take the advice of the pros on its face. Unless a whole lot of accomplished athletes are doing and saying the same thing, be weary.

Preparation

The second determining factor in strength/physique success is, of course, the preparation. By this I mean all of the training, diet, supplement, and lifestyle variables that influence performance.

What can you learn from the best in this regard? I think a lot, but you have to know what to look for. Preparation is such a complicated and interconnected endeavor that it does not pay to take small, precise pieces of advice at face value. Elements in a preparatory program are very interdependent, so that if one element is followed and the rest are not, or even if nine elements are followed but the tenth is not, disappointment and regression instead of motivation and success can result.

For example, you may read that a certain pro Bodybuilder eats 10,000 calories a day and trains each bodypart twice a week with 30 sets each time. Or you may read that a certain Powerlifter works up to a max every week, trains heavy six times a week, and makes regular jumps of 50lbs in each lift from week-to-week in regular training. If you try to replicate these elements in your own program, you may succeed, but you may also be very disappointed, if not overtrained or injured. What you have failed to integrate is the one (among many) ingredient that allows for them to succeed with such variables while you fail: supplement dosing. Just one such variable, small on its own, can lead to the disruption in application of a multitude of preparation strategies used by the best.

So if it is difficult to learn from the best by directly applying portions of their programs or even whole programs at a time, what useful information can be gleaned from their writings and interviews, if any? The good news is that much useful information can be extracted, but with a particular lens of examination. Only when looking at many dozens, if not hundreds of preparation strategies, can you start to employ this method; the method of commonality. By examining the preparation of multitudes of athletes, you will notice that, while many differences in strategy abound, many common practices are employed. These common practices are often the (not so) hidden gems of success in strength/physique sport. To quote Dave Tate “all the guys at the top are doing the same shit.”

Theoretically, these practices of preparation amount to the necessary (though not sufficient) conditions of success. Take a look at the best from bodybuilding and you will see that almost all of them train heavy, eat lots of food to grow, cut carbs and do cardio when they diet, train the big compound movements to put on size, train with a combination of heavy weights and high reps, and so on.

Just the same, almost every top Powerlifter does some sort of progressive overload training, works the assistance movements, focuses on technique as well as weights, is attentive to recovery, and takes periods of reduced training volume/intensity to peak and/or recover. While not giving you the sort of specific information about preparation that would be ideal in breadth and detail, an examination of the preparatory strategies of dozens of the best athletes can point you into the right direction of what you, at minimum, must do to succeed.

Genetics

Most importantly, an athlete who is to become one of the best must have the necessary genetics. We all know that genetics alone are not enough, and we all know that some champions are not the most genetically gifted individuals (Dave Palumbo would no doubt cite himself as an example). However, what must be understood is that the average genetic predisposition to muscle mass and strength increases (among other pertinent variables) is much higher in the group of elite performers to whom we look up when compared to the average lifting population.

This fact has several implications.

First of all, it implies that one should not expect the same results a pro got from running a certain program. Secondly, all advice from the best must be tempered with the knowledge that they, chances are, both adapt and recover faster and more completely from the same stimulus than the average lifter. When starting a program used by an elite athlete, it may be good policy to start with a fraction of the volume in the program, chart your personal response (undertraining, proper stimulus or overreaching) and adjust the volume from there.

On the opposite end of volume tolerance, some professionals may be so genetically “well-off” that they can be radically underdosing their training, with replication by an average lifter leading to under-training. For example, Melvin Anthony used to spend about 4 months out of the year not even training his arms directly. He would do the compound core movements, and that’s it. Come showtime, he always had phenomenal arms.

Is not training arms for 4 months out of the year the way to get arms like Melvin Anthony?

Probably not, but due to his genetic superiority in the area, Melvin was able to get away with it. To sum up, rarely does championship performance in the strength/physique worlds come from genetics alone (as hoards of YouTube trolls would have you believe). However, good genes are almost a prerequisite for championship outcomes. The intelligent consumer of preparation advice must be mindful of the interaction of genetics and other variables, so long as they are to extract meaningful information from the preparation strategies of the best in the sport.

The big picture

In general:

- Chance plays a significant role in sport success, and the advice of individual champions needs to be skeptically approached. The collection of information from large numbers of athletes can mitigate this problem and allow more clarity in the conclusions drawn.

- Common themes in preparation strategies are the fruit of an expansive evaluation of the programs of champions. Common approaches to training, diet, and supplementation can be valuable pieces of information, especially in hinting at what where you should start in your - own preparation. Quirky stuff can seem to work for one or two competitors, but if everyone has been doing the same thing for years (cutting carbs during dieting, for example), chances are that there’s some effectiveness in the approach.

- Genetics are a big, if not the biggest determinant of elite performance in the strength/physique sports. If you have good genetics, and you consistently run a reasonable preparation for multiple years, chances are you will be quite good at your chosen sport. For the consumer of preparation advice, this is important to remember, since the athlete(s) being sought after for preparation advice may not be preparing any better than the average performer, but simply have much better genetics. Furthermore, the consumer of championship advice needs to understand that genetic variables can change tolerances and demands of training, thus making the application of said advice a nonlinear process at best.

Outside of learning the basic science of training, seeking the wisdom of champions is the most important intellectual activity in strength/physique sport. But just like science, taking the advice of champions must be approached systematically and with a multitude of caveats. It makes for more work and more headaches, but it’s a small price to pay for improving your own preparation and seeing the progress you work so hard to achieve.

.JPG)